A Lithographer’s Legacy

By Andrea Perez Bessin

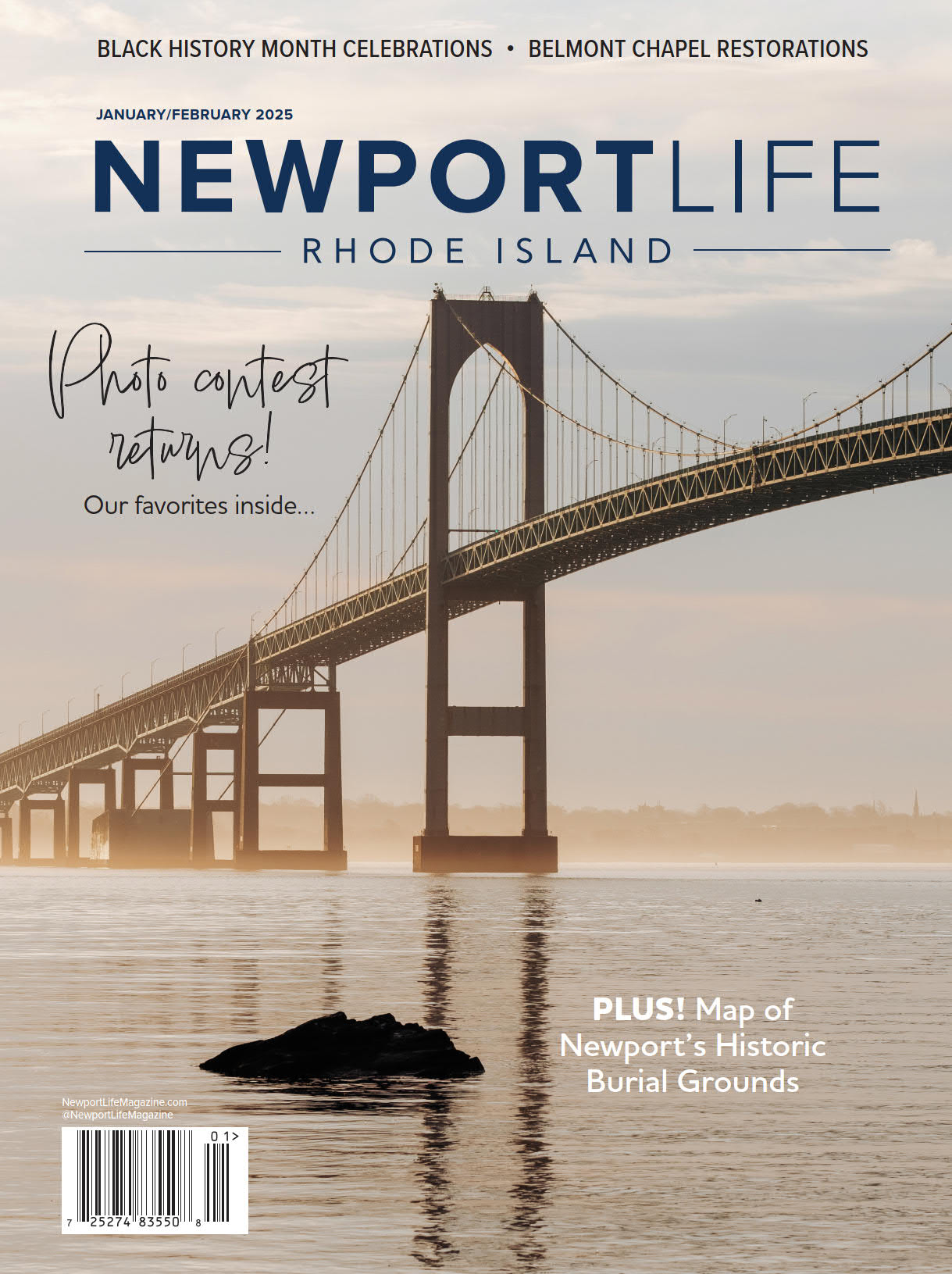

Latest exhibit at the Newport Art Museum features collected works of Joseph Norman

To know a lithographer is to know analchemist.

And Joseph Norman, a uniquely influential artist, is one of the most important lithographers of his generation.

As an artistic medium, lithography exists in the realm of the improbable: Oil and water assert their locations on the level surface of a stone to give way to an image that can be repeatedly transferred on paper for as long as the chemistry holds.

Joseph Norman’s particular alchemy extends well beyond the medium because he creates powerful amalgams of experience where the individual, the collective, the political, the literary, and the art historical converge to address personal narratives, historical events, social justice, and racial inequality.

Norman made Newport his home in the mid 1980s, and it was in Rhode Island where the artist built the foundation for a successful career in the arts that has spanned many decades.

A new exhibition at the Newport Art Museum honors Norman’s legacy.

“Joseph Norman: Works from the Permanent Collection,” features selections from series such as “Tenements,” “Berlin Autumn,” “Out at Home: Negro Baseball League,” and “Ole Jim Crow’s Scarecrows,” and is on display through April 16, 2023.

The exhibit is curated by Francine Weiss, who came across Norman’s work in the museum archives.

The exhibition opened Oct. 14 with a reception and panel discussion where Norman was joined in conversation with Bob Dilworth, painter, and Christopher Roberts, assistant professor of Theory and History of Art and Design at the Rhode Island School of Design.

The three men talked about artistic process, identity and its intersection with mark-making, and Norman’s influential time spent living in Rhode Island (he and Dilworth crossed paths in Providence in the early 1990s).

Their discussion offered a useful lens for considering the works on display.

A Homecoming

The opening reception hummed with lively conversation and a palpable sense of excitement that superseded the expected enthusiasm of a successful opening. It was, after all, a reunion with a beloved person who has left an indelible mark on the Newport community.

The conversation started with Norman reminiscing about his time in Newport, which began in the summer of 1986. He fondly recalled his early days in the city, working day jobs while gradually building a reputation as an artist. Among those jobs was a post at the Newport Art Museum.

Norman told those gathered that he was not only supported by the Newport community, but experienced real patronage here — people sought to know not just his work but his artistic vision, so they could nurture it in both material and immaterial ways. Many Newport residents went on to buy his work, becoming Norman’s first collectors.

As a result of this patronage, and through donations by generous collectors, the Newport Art Museum has amassed the largest museum collection of Norman’s work.

“It really takes a village to raise an artist,” Norman said, his voice warm and sincere, his tone that of a poet and storyteller, “and I had the best village [here] in Newport.”

“A beach!”

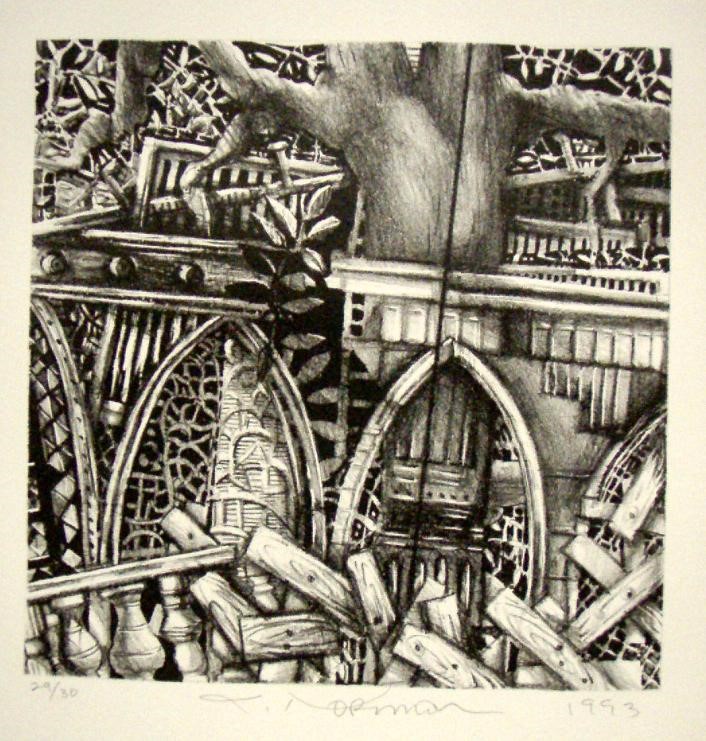

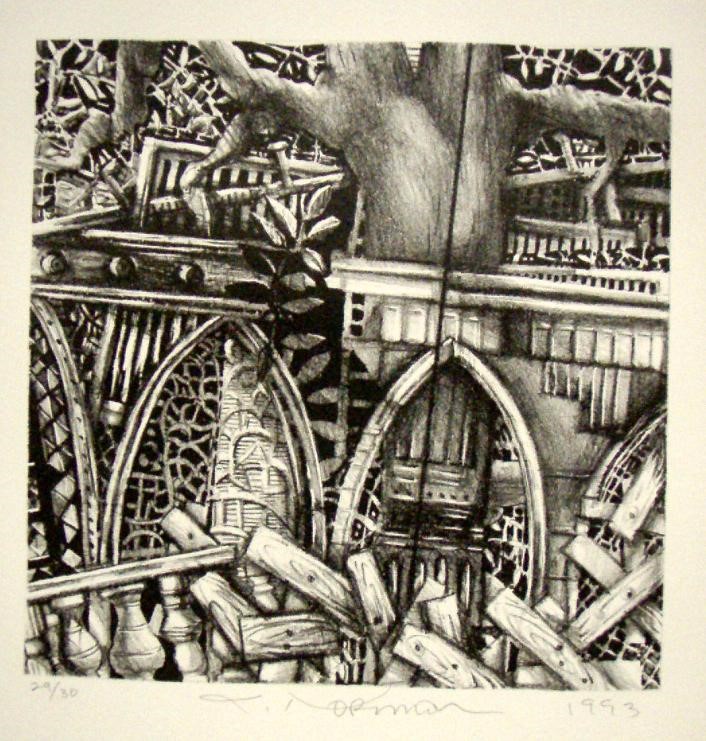

On display in the corridor towards the Ilgenfritz Gallery, four small lithographs depict densely packed fragments arranged in strong diagonals. Plants, ladders, heavily patterned gothic archways, shutters, ornamental balustrades, and white picket fences make themselves singularly apparent within the cluster of discarded objects.

The works, all printed in 1993, are part of a series titled Tenements: Chicago and refer to sites of illegal dumping where eroded architectural elements from the location’s long-gone affluent past and random detritus merge with overgrowth.

These pieces, inspired by Norman’s childhood neighborhood in the South Side of Chicago, hold the dual reality of locations that are both reflective of the violent indifference of companies that would dispose of harmful waste in Black communities — and as sites of potential and imagination for the people who resided in these communities.

The artist recalled an instance where he joined friends in the neighborhood to play at a “beach” — a vacant lot that overnight had been entirely covered in sand — only to find out later that the sand had previously been used to soak up a chemical spill —and was likely the culprit in a host of illnesses that subsequently befell the kids in the community.

Norman’s Tenements preserve a spirit of optimism and creativity through the inclusion of hidden stairs and portals, which present “a way out” to those who seek it, and are also reflective of the artist’s capacity to forge imagery that simultaneously holds beauty and difficulty.

Poetic Realist

On a wall in the main gallery, 40 images are arranged in a grid. Within the grid, a stylized fish head emerges to contextualize the rest of the images as abstractions of this original shape.

This lithograph from the Strange Fruit series is titled Kafka, and it engages the viewer as a witness to a metamorphosis, albeit a violent one. The work draws parallels between the dehumanization of the fictional character Gregor Samsa in Kafka’s “The Metamorphosis” and the very real and extreme violence of the white supremacists who murdered Emmett Till in 1955.

Kafka is emblematic of Joseph Norman’s distinctive style of poetic realism.

“Looking at hard issues and trying to make poetry of them, that has always been first and foremost the thing that stood out as something to try to accomplish in my work,” Norman told the audience on opening night. “I always thought it was okay to be a poet and a warrior.”

He is not aestheticizing racial violence, but strategically using symbols to confront the viewer with the brutal violence of white supremacy without surrendering the Blackbody to sensationalist reproductions of violence.

As Bob Dilworth brought up in their conversation, one of the great strengths of Norman’s work lies in his capacity to “use art to create these incredible, impossible conversations that we still cannot have in our living room or around the dinner table, these conversations about lynching, conversations about racism, conversations that are still very difficult.”

“Decoys”

Norman prefers to identify as only “Artist,” and if asked for specificity will call himself an “American Artist” or “Chicago Artist,” rather than “Black Artist.”

This is not to be interpreted as a dismissal of his personal identity as a Blackman, but rather a refusal to sacrifice the complexity of his vision and existence to the whims of institutional virtue signaling or neatly encapsulated monolithic views on Black art.

The monolith, a flattening of the spectrum of experiences that exist within a specific community, introduces the misconception of a uniform narrative and a singular paradigm of identity.

The artist met with these invisible boundaries of expectations when his Berlin Autumn series — inspired during a stay in Berlin where, among the towering white birch trees of the Tiergarten, he had an uncanny flashback to his upbringing in Chicago — was criticized as “too Eurocentric or not Afrocentric enough.”

Norman tackles the problematic ramifications of monolithic Blackness in the drawings Black Decoy #1 and Black Decoy #3. In each drawing, a black duck perches solitarily in front of a black background. The static nature of the central subject matter in both these works results in a highlight by contrast.

These images are emphatically loud in their stillness, especially in comparison to the swirling shapes and dynamic mark-making present in the others works on display in the gallery. The intentional rigidity of the form alludes to the inertness of an ornamental decoy duck completely stripped of any utilitarian function.

The idea for the Black Decoy originated from Norman’s personal experience as the only Black person in predominantly whitespaces. The artist extends the Black Decoy analogy to historical moments of strategic tokenism as forms of subterfuge used to quell demands for equitable institutional restructuring.

Legacy

Norman’s work remains as relevant as ever, whether considered within Newport’s own complex colonial past, or within topical conversations of race and identity— in the art world and elsewhere.

More than an interesting revisiting of a collection, it is an opportunity to engage with and honor Joseph Norman’s remarkable capacity to speak truth to power by way of metaphor — it is important that these symbols infiltrate the collective and spark conversations beyond the walls of the museum, so that anyone can see a birch tree and see more than just a tree.