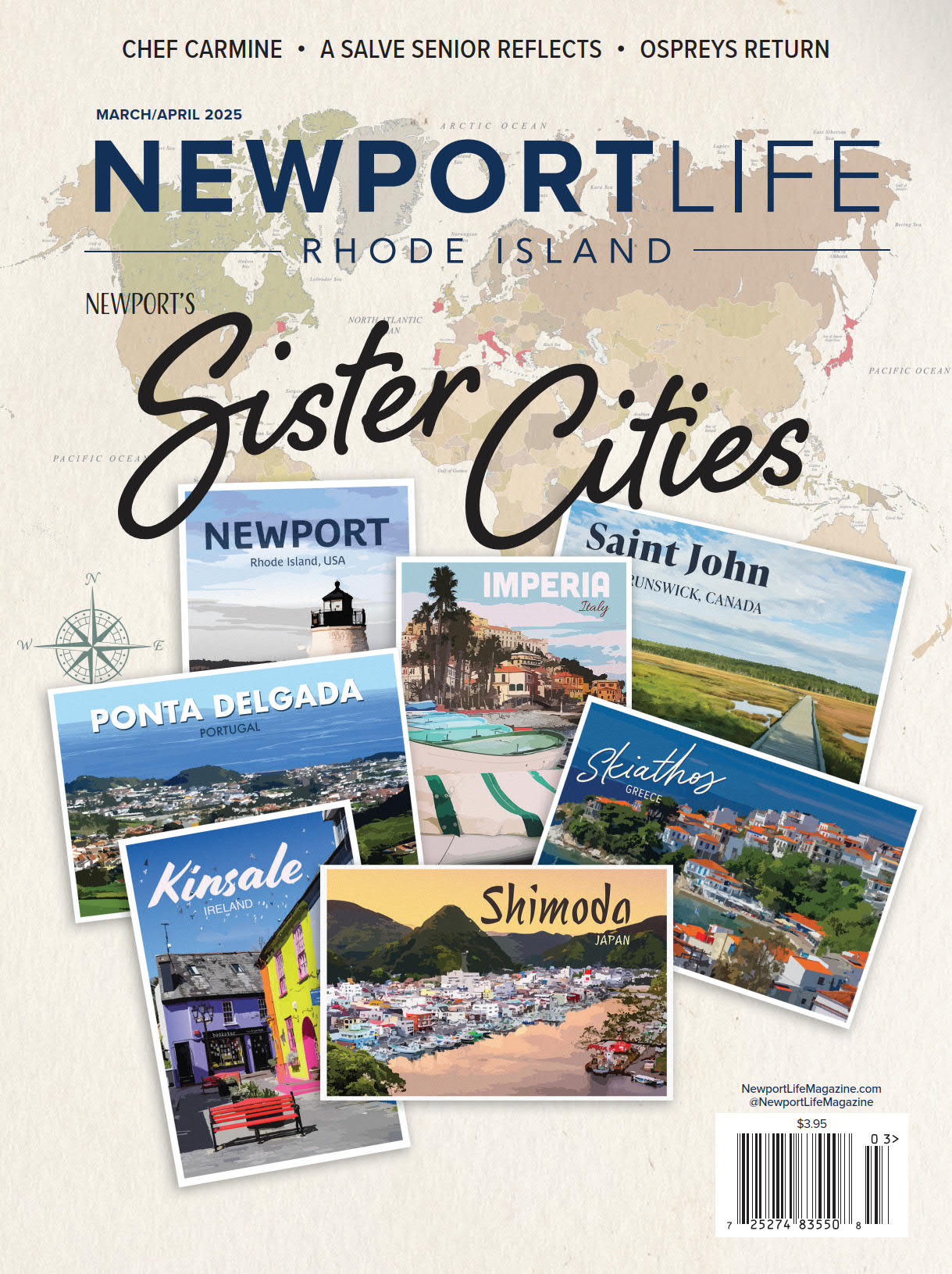

A Summertime Ritual: Clambakes are a timeless New England tradition

By Helena Touhey

Last summer, I attended my first backyard clambake. Having grown up on Aquidneck Island, the event felt like a milestone — a rite of passage as a lifelong New Englander, Rhode Islander, and island resident, somehow further legitimizing my stake in this place I call home.

Friends of mine in Newport had decided to host their first annual clambake, doing much research and delving into a longstanding regional tradition, one which many consider the quintessential summer feast.

The entire experience was a sensory one: the smoke rising from the earth, wafting through the August air, its scent as delicious as the suspense was palpable; there was the preparation, for which I was tasked with slicing an entire watermelon, which left my hands sticky and sweet, and myself better acquainted with some of the other guests; then there was the Grand Unveiling, that moment when the fire was put out, the tarp pulled back, and cheesecloth bags and metal bins uncovered from the seaweed-cushioned ground, their contents full of smoked potatoes, sweet potatoes, eggplant, onions, corn on the cob, peppers, chourico, mussels and, of course, clams.

The meal was delicious.

Dozens gathered around a collection of outdoor tables, decorated for the occasion, with guests getting up for seconds and thirds, the conversation stretching from dusk to dark.

It was not your average backyard barbeque. It was a good ole’ fashioned clambake.

* * *

Like any sort of lore, the conversation around the exact origins of the clambake oscillates from one theory to another.

What seems likely is that it evolved from the Native American tradition — particularly Wampanoag, a tribe that has inhabited this region for thousands of years, extending from modern-day Provincetown on Cape Cod to Aquidneck Island, and north to Plymouth, Massachusetts — of baking food in the ground and along the seashore. Once European settlers arrived, the practice evolved further into the clambake most think of today.

Kathy Neustadt’s “Clambake: A History and Celebration of an American Tradition,” was published in 1992 and remains a definitive guide on the subject. “However we may ultimately judge its role within Native American cultural practices, the clambake within a Yankee context has been consistently manipulated for a variety of purposes,” she writes. “Particularly during the late nineteenth century, when clambaking reached the zenith of its popularity, the clambake appears as a by-product of a combined romantic and capitalistic fervor.”

It is, in many ways and as she notes, an invented tradition that has firmly planted itself in New England culture, over time asserting itself as an established tradition. And that is, perhaps, one of its charms: that the clambake belongs not to a specific people but rather to a region and a coastal way of life.

On Aquidneck Island, there is Kempenaar’s Clambake Club in Middletown, which dates informally to the late 1920s and more formally to 1945, and McGrath Clambakes in Newport, established around 1960. Both are known for hosting seasonal bakes. Another annual tradition takes place at Castle Hill Inn in Newport, which hosts two clambakes every summer, and at Blithewold in Bristol.

Clambakes at Kempenaar’s come to life in 30-gallon pots that get assembled in a “big box” filled with seaweed. “We throw the food in and let it cook,” says Chuck Kempenaar, emphasizing that clambakes are really pretty simple. “It just gets done — it’s not a lot to explain.”

The key ingredients have remained the same: lobsters, steamers, mussels, corn, potatoes, onions, chourico. On average, roughly 120-150 pounds of clams are used for a bake attended by about a hundred people.

The club hosts a community clambake every year on July 3, which is attended by about 450 guests each summer. “A lot of the same people get tickets every year and make it a big family thing,” says Kempenaar, noting the event started sometime in the 1990s.

“When the bake bell rings, we’ll serve you a feast of clam chowder, steamed clams, mussels, a whole lobster (or charcoal broiled chicken or steak), chourico and much more,” reads a description on the club’s website. “Come early and enjoy our country cheese, entertainment and clam cakes.”

Another summer tradition is the annual clambake held every August to celebrate the arrival of a new international class of military officers at the U.S. Naval War College in Newport. That bake has been taking place for at least 65 years, says Kempenaar, who took over the family business in 2007 and began working there as a youngster around 1995.

His first jobs were “parking cars or husking corn or raking the rocks — whatever you got to do,” he says. Now, he’s joined in work by his wife, Ashley, along with his brother and a cousin.

“It’s really something else,” says Kempenaar, adding that the club hosts about 120 clambakes a season.

His great-grandfather, Esau Kempenaar, an immigrant from the Netherlands, founded Boulevard Nurseries in the early 1900s off Valley Road in Middletown, which is where Kempenaar’s Clambake Club has been located for nearly 80 years, nestled into a valley grove of evergreens.

Each summer, Esau would host a clambake for his workers and family, which became an annual tradition. It gradually expanded to include other horticulture clubs and nursery associations and grew to include the War College and events for police officers and chiefs.

Now the club hosts weddings, rehearsal dinners, and reunions, among other events. The facility can accommodate a gathering of 700 or more, and guests can enjoy a game of horseshoes, volleyball, or bocce on the grounds.

“It’s a little hidden gem of the island — your own little getaway,” says Kempenaar.

* * *

Over at Castle Hill, Executive Chef Jennifer Backman is behind the annual clambakes, this year held June 27 and July 17. The bakes, which began in 2015, are billed as “a New England tradition like no other,” held rain or shine, and served buffet style. Tickets cost $150.

“Castle Hill Inn’s clambake is traditionally prepared over a wood fire, where the lobsters, local corn and potatoes are cooked in custom-built stainless-steel cages, lined with a seaweed indigenous to our region called rockweed. Rockweed is perfect for this application because it has pockets of saltwater that burst during cooking, helping add flavor to everything,” says Backman, who notes the bake first started as a way to celebrate the local bounty and techniques first utilized by the Wampanoag and Narragansett tribes.

The Castle Hill menu includes clam chowder and clam cakes; 1¼ pound lobsters; BBQ chicken; littleneck clams, smoked in seaweed broth; chourico and peppers; potatoes, onions, butter and sea salt; three bean salad; vegetable slaw; panzanella salad; jalapeno-cheddar cornbread; and traditional apple pie.

And in Bristol, Blithewold has been hosting an annual family clambake for over a century on the Great Lawn of the 33-acre estate. This summer, that bake will be held Aug. 22 in partnership with McGrath. Tickets cost $100.

“Feast on a traditional Rhode Island clambake while you relax and enjoy sunset as Blithewold guests have for generations,” reads a description for the event, which hosts 100 people, rain or shine. The menu reflects the traditional fixtures of a clambake: 1¼ pound Rhode Island lobster, chowder, salad, steamers, PEI mussels, corn on the cob, potatoes, chourico, barbecued chicken, and watermelon.

There is another historic site on Aquidneck Island where clambakes continue to be served, but most of us probably won’t ever slurp a steamer or crack open a lobster there. The Newport Clambake Club is a private social club on four acres at the southernmost tip of Easton’s Point in Middletown. Founded in 1895, its first clubhouse was built sometime between 1903 and 1907.

In 1995, the U.S. Department of the Interior listed the Newport Clambake Club on the National Register of Historic Places. According to the NRHP registration form, “the Clambake Club of Newport was founded by some of Newport’s most prominent members of society in (an) attempt to escape the pretensions and formalities of the Bellevue Avenue social scene.” Cornelius Vanderbilt, Maximillian Agassiz and Robert Goelet were among the early members.

Charles Oelrichs, a club president in the early 1900s, wrote a letter to Bradford Norman in 1930 describing the club’s origins. There were several men, Oelrichs wrote, “who hungered for the succulent clam and its accessories and not, mind you, served in the villas of the rich but in the open and in the simplest manner — hence our club.”

* * *

Day-of preparation for a clambake, especially the backyard variety my friends hosted, entails a fair amount of work.

There is the soaking of the tarps (my friends opted for bedsheets and used trash barrels), filling buckets with water to keep around the fire pit, gathering metal rakes and fire pokers, collecting kindling and bonfire wood (including some driftwood), and ensuring you have enough seaweed. Particularly rockweed, which is best gathered on the day of the bake at low tide and is usually found on hard surfaces like rocks, shells and dock pilings. Rockweed is traditionally used in a clambake to help create steam and is thickly applied to the fire once it has burned down to the coals.

In “Cape Cod Wampanoag Cookbook: Wampanoag Indian Recipes, Images & Lore,” printed in 2001, Chief Flying Eagle, Earl Mills Sr., of the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe, writes: “On the day of a clambake, rockweed is collected. My family prefers to collect this greenish brown seaweed … at medium tide, because the swift current keeps the rockweed clean and free of algae.

“Rocks are chosen for uniformity of size and shape,” Mills continues. “New rocks are required for each clambake since they lose temper, or their ability to hold heat, once they’ve been heated. The rocks are placed on the ground at the site chosen for the clambake.”

“Traditionally, rocks were arranged in a circle, but in modern times the shape of the mound accommodates the shape of the firewood that is collected. Circles have special significance to my people, and it’s easier to work with a circle since the food can be reached from every edge of the mound,” he explains. “On the day of the bake, dry wood is piled on top of the rocks. A hose is always kept nearby to control the fire and keep the rockweed wet. Meanwhile, the food is prepared.”

In Newport, after spreading a roughly 4-inch-thick layer of rockweed across the coals, my friends placed the food in the following order: potatoes, onions, chourico, corn, mussels and clams, red pepper, fennel, eggplant. They reserved a few potatoes to place near the outside of the tarp, so they could easily be checked and used to monitor if the bake was done.

The pile was then covered with more rockweed (“It’s very important to add a layer of wet rockweed between each layer of food,” explains Mills in the cookbook he wrote with Betty Breen. “Steamers are added last over a thin layer of rockweed. [And then] rockweed covers everything.”). A wet tarp was placed over the mound and sealed with rocks.

At that point many of the clambake guests headed to a nearby beach for a quick swim. It can take anywhere from one to three hours for the hidden feast to cook. During that time the canvas is periodically splashed with water to ensure it doesn’t catch fire or burn.

Mills notes that it is a combination of the clams breaking open and spilling their juice and the saltwater released from the rockweed that steams the food. There’s plenty of prep work that takes place before the bounty of food is ready for the steam bath beneath the tarp. Ears of corn must be shucked, vegetables must be washed, peeled and chopped, mussels must be scrubbed, and clams must be rinsed of sand before the bake is sealed.

Then the focus turns to slicing watermelons and lemons, setting the tables with plastic bibs and stacks of napkins, and ensuring the beverages are iced and plentiful. When the food is ready, one guest is tasked with the important role of melting sticks of butter, pouring it into small bowls and getting them on the tables while still warm.

* * *

“More than a century’s worth of romantic, sentimentalized, and nostalgic notions surrounding the clambake have enabled it to continue as a powerful, multi-faceted symbol into the present day,” writes Neustadt, noting the plethora of articles on the subject that appear in publications, especially come summertime. And especially in New England, along with the abundance of clambakes held for weddings, class reunions, fundraisers and other events.

All of this, she says, has kept the clambake a vital tradition: “There is every reason to believe that in gastronomic as well as symbolic terms, the history of the clambake is far from over.”

And that, it’s worth noting, she wrote 32 years ago.

It seems safe to say the clambake has remained an active cultural tradition and summertime ritual, one that continues to conjure an idyllic image of coastal life and is, essentially, the same in practice.

Which is perhaps another of its charms: the nostalgia a clambake evokes is not just that of a bygone era but also a sense of timelessness. Which, in these days of relentless technology, is a welcome escape. Especially on dreamy summer evenings, when being able to enjoy a good ole’ fashioned bake is one of life’s simple pleasures.