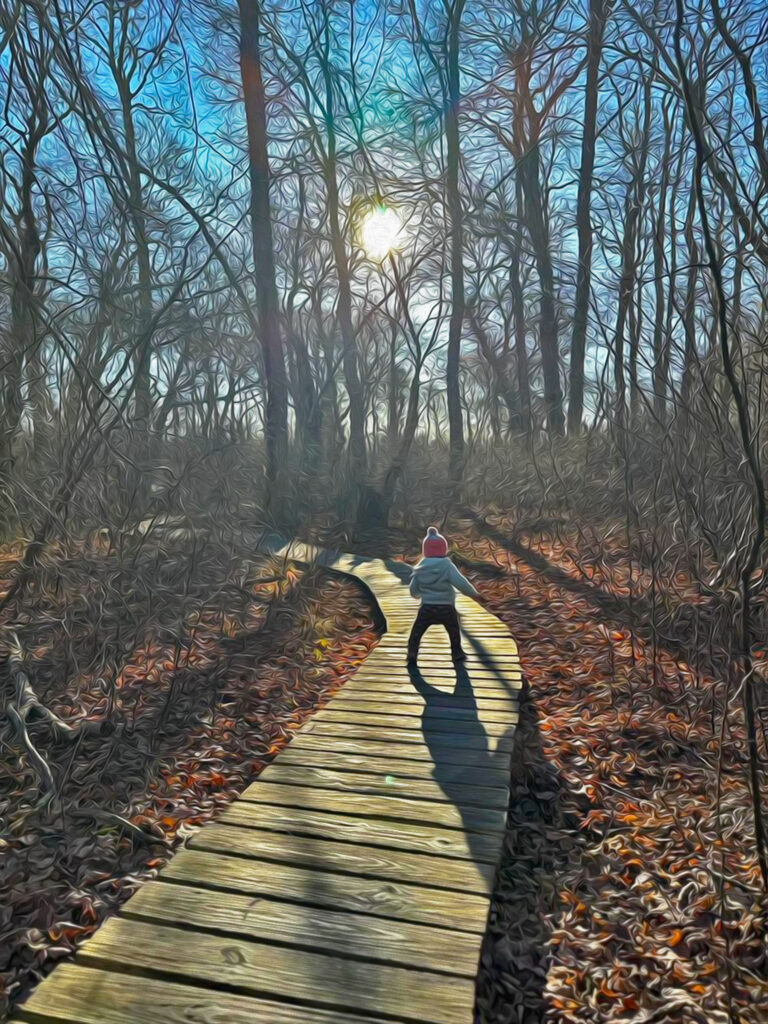

Essay: A walk in the woods with you

By Christopher Reeves

The following is an essay, written as a letter, by Christopher Reeves and addressed to his young daughter, Ardenna. Reeves and his family live in Portsmouth. They moved to Aquidneck Island 10 years ago from Monterey, Calif. Reeves is a sailor, science writer, and father. He is a captain aboard schooners in Newport Harbor during the summer and a dad of all trades in the winter.

Dear Ardenna,

We pause our hike to take in the scene, silencing the bright squealing crump of boots in fresh snow. Icicles jut from rock faces — revealing the subtle subterranean creep of water. Hollies stretch their branches in evergreen pirouettes against a monochrome stage. It’s been almost a year since we’ve had these woods to ourselves. Right here, at the edge of this brook in Tiverton, is where you and I were paced by a barred owl who drifted on silent wings from tree to tree, watching us, the last time we visited this spot.

Back then, I was in love with — and a little terrified by — a months-old daughter who I once feared may never come to be. After five years of painful medical intervention, you were finally in our lives, but you were so vulnerable and there was a pandemic on. It was fully winter before we began to venture out of the house. You wouldn’t sleep outside the arms of your mother and I, so I carried you under my jacket through Rhode Island’s forests to nap, hoping that the sensations of nature would wend their way into your sweet slumber. You stirred awake when the owl alongside us settled on a branch at a fork in the trail. The owl was a tuft of winter-fat gray with black-pool eyes framed by crisp sky among the squirrel nests, conspicuous now in the bare boughs of ash and maple. We all stood staring at each other, and I was more at home with you and this owl in an empty wood than I have been in almost a decade of living here.

We are different people now.

Summer snapped into Fall, which itself has ebbed. Winter’s powder blanket once again covers the insulating decay of fallen leaves on the forest floor. You ride atop my shoulders, making it easy to set you down to explore on your two toddling feet in little boots of your own. I scan the trail ahead for interests and dangers alike. What was a vernal pool two months ago is now a frozen window framing leaf litter and frogs — frogs who hang in suspended animation, letting icicles grow in the spaces between their cells while the rest of the world contemplates the cold.

As early as four months old, you were fascinated with the tinkling movement of this water, waking to peek out of my jacket to watch its flow. Now, you waddle off toward the pool in your cowboy gait and I’m startled at the thought of how far it is to hike back to the car with a frostbitten baby should the ice prove to be too thin. You blurt a cry in protest when I steer you back to solid ground — I need you to learn to walk a little better before you learn to swim.

The networks of tree roots exposed by shallow bedrock are tough for a toddler to navigate, so you grip my index finger for balance, chanting “Wa, wa, wa,” for “walk, walk, walk,” and let out an exuberant, “oooh!” every time you take a big step. You, like me, love sharing your discoveries. You hand me an ochre-veined leaf. “Dada, lee!”

“That’s a beautiful leaf.”

You point at a turgid tuft of green combing through the slow slip of bubbles under clear ice; “Dada, mo! Mo!”

“Yes, Love, green moss.” The forest sculpts your burgeoning vocabulary even as it hones your balance.

While I know you’re not forming episodic memories just yet, I hope that spending time in this forest seats its sensations in your soul the way that fresh kelp, salt fog, and the quiet drum of foot-falls on redwood loam flow within me. We are inextricably interconnected with nature, and I hope you feel that communion as intimately as the movement in your own limbs.

It seems strange to your mother and I that you aren’t living in the environments that forged us into your parents; not the shores of California where I grew up and where your mother and I met, or even in her native New York. You’re a Rhode Islander. The particular salt and flood of Narragansett Bay is your home water. You’ll have the softer smell of clambake rockweeds in your nostalgia instead of pungent wracks of giant kelp; the crunch of deciduous leaf litter underfoot instead of redwood loam; and the fleeting fervor of seasons.

The forest shook free its green and quelled the riotous life of summer in the short time between your first tentative steps and the dauntless little boot-prints you’ll leave in this subdued landscape today. Before long you and I will watch the bruisy contours of skunk cabbage unfold in Spring swamps and a succession of goldfinches arriving among matching daffodils before the forest foliage riots again come next Summer. I will be there to show you where to reach when you learn to climb the trees and to give you words for the life that follows alongside your path.

Being “local,” born to a place that you enjoy, doesn’t make you special; just lucky once. I no longer wonder how to raise you in a land that is not the stuff of my own soul. After meeting your mother and now, after your arrival in our lives, my home is wherever you two are. Today, the embodiment of all my hopes, standing a foot and a half tall and larger than life, is towing me by the finger through an intricate landscape that I am lucky enough to be born into as her father.

A sudden wind roils through the naked maples overhead, sending cardinals bounding from a copse of crimson winterberries.“Dada!”

“Yes, Love?”

“Bir!”

“Yes! Did you see those bright red birds?”

Your grip tightens around my finger, “Ooh!”

“Big step!”

“Dada, sti!”

“Yes, Love, that’s a lot of sticks!”

We toddle off into snowy woods together, at home in the company of owls.

IF YOU GO

The areas of Tiverton and Little Compton offer fantastic opportunities for short hikes in a series of natural reserves. The hike featured in this essay is the Sin and Flesh Brook trail in Fort Barton Woods, Tiverton. Reeves’ favorite hikes on Aquidneck Island include Sachuest Point National Wildlife Refuge, Melville Pond, and the incomparable Norman Bird Sanctuary.