Ocean Race Around the World

By Sean McNeill

The Ocean Race began on Jan. 15 and arrives at Newport in May, ideally led by local favorites Charlie Enright and the 11th Hour Racing Team

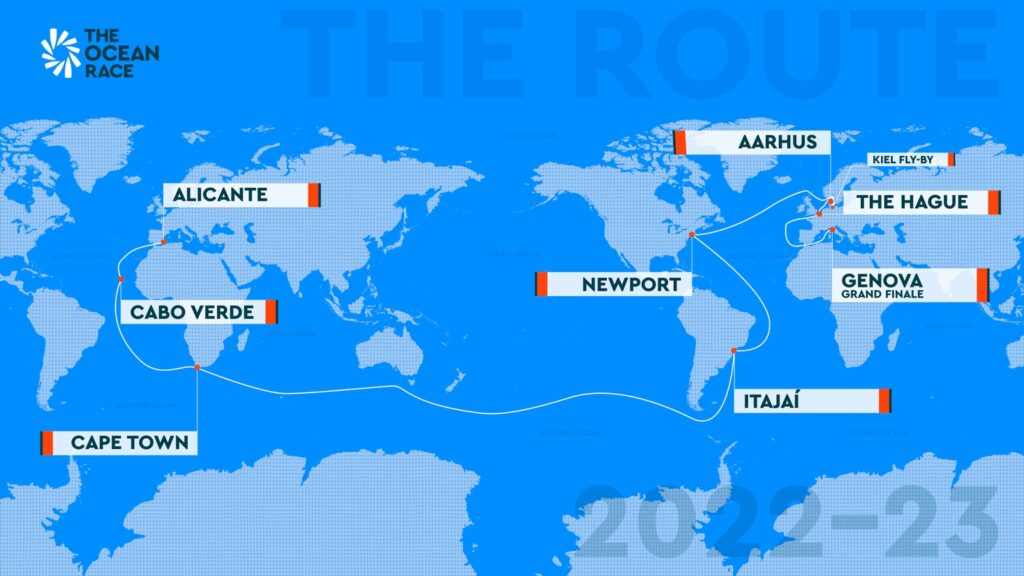

Sometime in May, probably between the 8th and 12th, an intrepid fleet of five semi-foiling 60-footers will descend upon Newport for the Leg 4 stopover of The Ocean Race, the crewed circumnavigation race. If the conditions are ripe, the yachts could come speeding into town with hulls almost clear of the water.

The new breed of 60-footers is that fast.

Ideally, Charlie Enright and the crew of Mālama, the entry of11th Hour Racing Team, will lead the fleet into town. Enright, the 38-year-old globe-galloping skipper who was born in Bristol, is back for his third lap of the planet with funding from 11thHour Racing, the Newport-based sustainability organization that is also a Premier Partner of the race and the founding partner of its sustainability program. (11th Hour Racing is also the co-host, along with Sail Newport and the State of Rhode Island, of the Newport stopover; see sidebar.)

Enright has collected a lifetime of experiences in his two previous laps of the planet during The Ocean Race. One of his all-time highlights was leading the fleet around Cape Horn during the 2014-15 race, when he was the youngest skipper (30)of the youngest crew (average age of 32). They surfed across the Southern Ocean to round the rocky outcrop by 5 nautical miles and savored the accomplishment with cigars in 25-knot winds where the South Atlantic Ocean converges with the Southern Ocean.

A couple of months earlier in that race, his Team Alvimedica stood-by a stricken competitor that had run aground in the Indian Ocean on the Cargados Carajos Shoals, essentially a coral reef flat some 230 nautical miles northeast of Mauritius. Enright and crew were on stand-by for eight hours before the crew abandoned ship and was rescued by coast guard authorities from the nearby island Íle du Sud, which is also known as St. Brandon and part of Cargados Carajos Shoals.

In the 2017-18 race, Enright and crew won Leg 1. But later in that race the yacht (sans Enright) was involved in an unfortunate collision with an un-lit fishing boat approaching the finish of Leg5 into Hong Kong in the middle of the night. The resulting damage to the bow was significant and meant that it would miss racing the leg to New Zealand while it was shipped there to undergo repairs.

“In the first edition, we didn’t know what we didn’t know, but that was also a beautiful thing in a lot of ways,” says Enright. “In the second edition, it felt like we were doing a lot with a little, until we ran into some unfortunate circumstances. Both campaigns were always a little late and underfunded. Now we feel like we have the support and the runway.”

The Ultimate Crewed Race

With the support of 11th Hour Racing, Enright leads the only American-flagged entry in the 14th edition of The Ocean Race, the circumnavigation race inaugurated in 1973-74 as the Whitbread Round the World Race. More recently, from 2001 to 2018, the race was known as The Volvo Ocean Race, under whose banner six editions were held. Volvo Group and Volvo Cars, the co-owners, sold the rights to the race after the last edition. It is now owned by The Ocean Race SLU, a Spanish company headed by Swedes Richard Brisius, Johan Salen and Jan Litborn. Brisius and Salen are past competitors in the race and, with Litborn, have organized two winning teams. Volvo Cars remains a Premier Partner.

Since its inception, The Ocean Race has been the ultimate crewed offshore race. Crossing the equator twice while rounding two of the world’s great capes — Cape of Good Hope and Cape Horn — and surviving the Roaring Forties and Screaming Fifties, the part of the race that traverses the Southern Ocean, are just some of the challenges the race presents.

Leg 3 is the marathon leg of the 14th edition, 12,750 nautical miles from Cape Town to Itajaí, the longest leg in the race’s nearly50-year history. Longtime fans of the race might notice that the course doesn’t include a stop in Australia or New Zealand. The race has a long association with the Southern Hemisphere sailing nations, calling in one or both countries in 12 of the 13 previous editions of the race, and four overall winning skippers are New Zealanders.

The Covid pandemic has played havoc with this iteration of The Ocean Race. Originally scheduled for 2021-22, the route included stops in New Zealand and China. Each country had strict regulations against international travel, which prevented the completion of host port agreements because the countries couldn’t predict when they would re-open to international travelers. It all resulted in the leg from South Africa to Brazil, a marathon estimated to last at least one month.

“That leg comes down to the reliability of the boats,” says Enright. “In the single-handed ‘round the world race (Vendée Globe), it’s a race (from France) to the Cape of Good Hope. In the Southern Ocean there’s a sort of tacit agreement among the skippers to get to Cape Horn safely, and then start racing again. Our boat is crewed, and with more people, there’s the temptation to push harder. Finding that line and making sure everyone gets through that part of the world safely is going to be a hairy chapter.”

Onboard Mālama

Joining Enright in the international crew of Mālama are Jack Bouttell of Great Britain, Francesca Clapcich of Italy, navigator Simon Fisher of Great Britain, Justine Mettraux of Switzerland, and onboard reporter Amory Ross of Newport. Enright’s previous co-skipper Mark Towill of Hawaii, who sailed the past two editions, is the team’s CEO and staying ashore this race.

The five active sailors (as the onboard reporter Ross isn’t allowed to assist with the sailing of Mālama unless there’s an emergency) have the combined experience of 12 Ocean Races. Fisher is the most experienced, having done each of the past five editions, dating back to 2004-05. He also navigated for Enright in the 2017-18 race aboard Vestas 11th Hour Racing.

“There’s a quote about The Ocean Race getting in your blood — and it’s true. It’s the one sailing event that I can remember watching as a kid in the ‘80s and saying, ‘I want to do that!’,” says Fisher. “This race is particularly interesting because we’re back in a development class. Every decision we make pre-race will impact how we perform on the racecourse.”

Besides the new race name and new racecourse, the boats that the sailors will jockey into town are also different from the previous race. The VO65, a race-specific design with a canting keel and daggerboards that helped it track a straight line, has been replaced by the IMOCA 60, a semi-foiling 60-footer. Although five feet shorter than the VO65, the IMOCA 60 is the world’s leading monohull development class and is the preferred design of single-handed racers. (As many as five VO65s could take part in The Ocean Race VO65 Sprint Cup, which will count Legs 1, 6 and 7 and the respective In-Port Races).

The IMOCA 60 was adopted for the crewed The Ocean Race due to its great speed potential and developmental design features. The IMOCA 60 is powerful, with a mast height nearly95 feet above the water. It also features hydrofoils in place of the daggerboards of the VO65. The foils, 3 to 4 meters (9 to 13 feet)from the hull intersection to the tip, help the design lessen its displacement while providing lift and preventing leeway. The design also has a canting keel for added stability and water ballast tanks to improve trim.

The IMOCA 60, however, is not a hydrofoiler, like a Mothone-design or an AC75 monohull. That is because the twin rudders on the IMOCA 60 are fin rudders. Fixed on both the starboard and port side of the boat, the rudders jut straight down from the hull intersection. The lack of an end plate and elevator flaps at the bottom of the rudder, such that would form an inverted T shape, prevents the IMOCA 60 from being a full hydrofoiler.

Enright and the crew of Mālama, which was designed by French wizard Guillaume Verdier and built in France, had logged close to 25,000 nautical miles from the boat’s launching in August2021, to last December. They crossed the Atlantic Ocean four times and spent months training off their base in Concarneau, France. In a milestone moment last summer, while sailing from Newport to France, Mālama racked up a 24-hour run of 560.54 nautical miles at an average speed of 23.36 knots (27 mph). While that speed is barely faster than the 25 mph speed limit posted around Newport County, it’s an encouraging indicator of the design’s performance capability, which could top out at 35 to 40knots (40 to 46 mph).

“We designed a boat and built a boat. We’ve got to get that boat into a sweet spot,” says Enright. “It’s about design and development, certainly, but also reliability and hours on the water. You can have the fastest thing in the world, but if it’s not proven and doesn’t finish, it doesn’t do you any good. We’re hoping this race falls in the sweet spot for this platform.”

Good Luck and Strong Stomachs

Succeeding in a marathon such as The Ocean Race requires a large amount of skill as well as a bit of luck. Getting a 60-footfoil-assisted monohull around the world with crew is easier said than done. The foils are a boon to performance, but they are also a constant worry for what unseen floating objects they might snag. And if one breaks, your hopes on that leg, if not the race, are dashed, depending on the severity of the damage.

The Ocean Race has never been for the faint of heart, but by many accounts this year’s race will be more taxing on the body than ever before. The IMOCA 60 is a physical machine, a violent ride when blasting along on the foils. Water isn’t soft, and although the foils lessen the boat’s displacement (the hull is more out of the water), the hull is usually slamming into some portion of the wave when sailing at high speed.

Reports of motion sickness among the crew have been numerous during training.

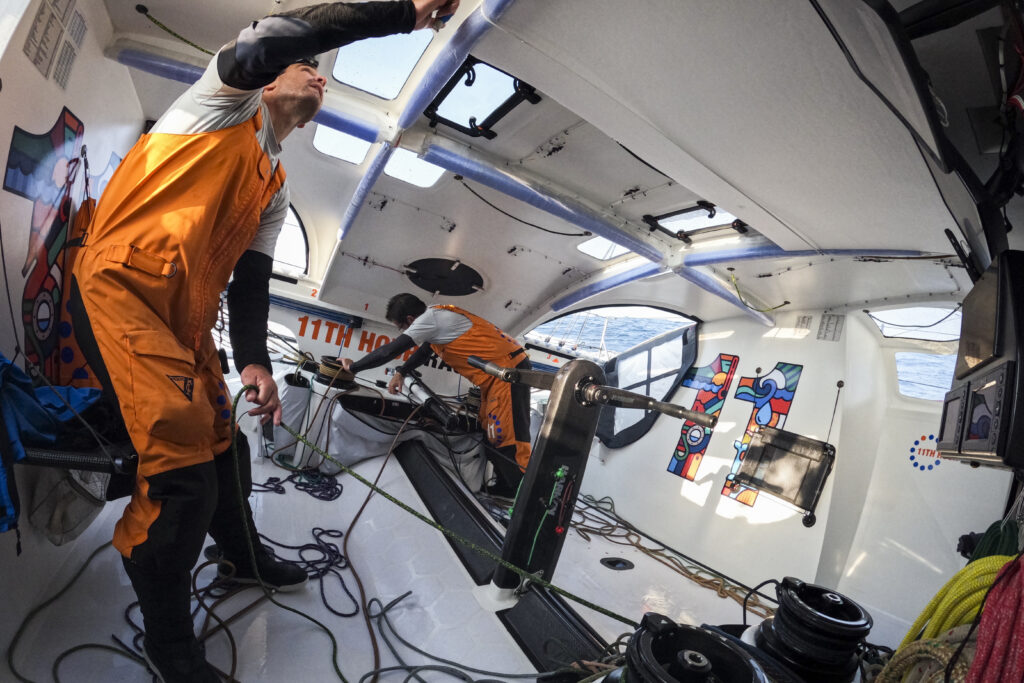

Forget the idea of creature comforts such as cabin lights and berths below decks. As the boats are constructed of carbon fiber, the interiors are pitch black. Each sailor wears a headlamp to see. They likely will be sleeping on sails, makeshift pipe berths or the hull itself. In past races, when maxi boats of 80 feet or longer were de rigueur, some entries were equipped with heaters to warm wet clothing.

Not anymore.

And, on the maxis, you could usually get a well-cooked meal. Not anymore. The sailors will be living on freeze-dried food — the water for which is boiled on a one burner camping stove — and protein bars.

One can also write off going topsides for a breath of fresh air. The IMOCA 60s are designed with the cockpit mostly enclosed. In many cases, like on Mālama, just the aft end is open to enter and exit. The canopy over the cockpit is welcome, as it keeps the sailors sheltered from the elements, in particular the thousands of gallons of sea water washing over the deck with the force of a firehose. But it means that they’re always enclosed, that they helm the boat (when the autopilot isn’t helming) looking out of a plexiglass bubble. All sail-handling controls lead back to the cockpit, with the intention of not having the sailors on deck, as it would be easy to be bounced overboard.

As sailing is a very sensory sport, there’s an element of sensory deprivation that requires adjustments.

“The roughness always depends on the conditions you have, but for sure there are changes on these new boats,” says Mettraux.“Everything is more closed, they go faster, you have to be careful how you move onboard; hold on. We spend quite a bit of time on our knees, or if below, try to find a place to sit, maybe the bottom of the boat, to eat or do stuff you have to do down below to make sure you’re not going to go flying through the boat. It’s not all the time like this. Sometimes it’s light and easy, but for sure the faster you go the more violent it is. Life is a bit less comfortable for sure.”

The name of 11th Hour Racing Team’s yacht is derived from Hawaiian lexicon. “Mālama” essentially means to care for, protect and preserve. While those values are central to 11th Hour Racing’s ocean-based sustainability message, the name is also apt for the crew racing aboard the yacht. Because to lead into Newport and have a chance at winning The Ocean Race, they’ll have to care for, protect and preserve Mālama in some of the world’s harshest environments.

The Newport Stopover

For the third consecutive edition of The Ocean Race, Newport will host a leg stopover. This time it’ll be Leg 4, which begins in Itajaí, Brazil, on April 23. The leg measures 5,550 nautical miles and is estimated to take 17 days. The Newport stopover is co-sponsored by 11th Hour Racing, the sustainability organization that’s advancing solutions and practices that protect and restore the health of the world’s oceans, Rhode Island’s public sailing center Sail Newport, and the State of Rhode Island.

One experience that 11th Hour Racing Team skipper Charlie Enright and many other sailors always enjoy is sailing off Newport. Whether it’s their first time or 100th, Newport holds a special allure. “The backdrop is spectacular and starting or finishing any race in Newport is always special,” says Enright.

The race’s stopover has been special to Newport, too. The two previous visits of The Ocean Race drew more than 230,000 people to the City-by-the-Sea each time in the middle of May, usually a down time in Newport. The visit in 2015 had an economic impact worth $47.7 million.

“We know how good it is for the hospitality industry and the town during the shoulder season of May,” says Brad Read, the Executive Director of Sail Newport. “Surveys show that we get a lot of visitors from southeast New England, but also down the East Coast and up into Canada. This type of event is great for Newport in the spring, it gives a great head start into the summer season.”

Many of the activities around the race will be held at Fort Adams State Park. The Ocean Live Park will be an interactive zone with a message of ocean sustainability. There’ll be food and beverages served, big screen monitors, sponsor pavilions, and opportunities to view the racing yachts berthed at the North Pier. The In-Port Race is scheduled for May 20, and the Leg 5 start for May 21. All racing will be viewable from the north lawn at Fort Adams. (For more information visit www.theoceanrace.com or www.theoceanracenewport.com.)

“We look forward to welcoming the out-of-town visitors as well as the extraordinary athletes and the technological marvels of the IMOCA60s,” says Read. “The beating these men and women take in boats going 40 mph is a feat of physical and mental achievement. It’s hard todo what these sailors are doing, and we can’t wait to greet them.”