Remember Salas’? Muriel’s? Mack’s?

Five Newport restaurants we still miss today

By Andrea E. McHugh

It’s amazing how some of the most ordinary things in our childhood become our most treasured memories. Think of mom and dad taking you out for a lobster roll; piling into a vinyl booth with your teammates for ice cream after practice; feasting with your family on a double order of fish and chips and fighting over the last french fry.

Countless Newport restaurants have come and gone over the past century; it’s the nature of a hospitality-driven destination. But some restaurants leave an indelible mark in your memory long after the doors have closed.

While there are many contenders for the favorite restaurants of yesteryear, we’re featuring five eateries that undoubtedly bring back memories for many.

“Mack’s was the place to be!”

Mack’s Clam Shack

(1960’ish–late 1970s | Lee’s Wharf )

& Dry Dock Seafood

(1982–2007 | 448 Thames St.)

Mack’s Clam Shack scratched the fish and chips itch for everyone from fishermen to families in the 1960s and ’70s. The no-frills brick building fronting a fishing pier was originally home to Tallman and Mack Fish Trap Co., a fish-packing operation incorporated in 1917 across from the formerly bustling Williams & Manchester Shipyard.

“Mack’s was the place to be!” says Joann Carlson, owner of Jo’s American Bistro on Memorial Boulevard. Carlson’s grandparents owned Tallman and Mack; her aunt and uncle, Paul and Anna Delgado, owned Mack’s, and her parents, James and Grace Abante, owned Dry Dock Seafood, a Thames Street restaurant that opened in 1982 and remained a local favorite for 25 years.

Carlson says she started working at Mack’s when she was just 16 years old, first at the take-out window, then working her way up to server (although she didn’t let that go to her head). She still spent plenty of time washing and picking lobsters for the lobster rolls and cooking up french fries, whole-belly clams and fish and chips in the deep fryer. “An Italian family? Yeah, we all had to know how to do everything,” she says with a hearty laugh.

On a typical day or night, she says, folks would pick up their order from the window, add some malt vinegar if desired, stroll over to the fishing pier, and nibble on the hand-cut fries, clam cakes or fried jumbo shrimp right out of the brown paper bag while dodging the seagulls that commonly swooped in.

“With a crushed seashell parking lot and picnic tables that looked like they were going to fall apart, it was the most unpretentious restaurant you ever did see,” Carlson says. In later years, Mack’s Clam Shack added a dining room along with a pool table and pinball machines.

Symbolic of the unfussiness of the restaurant, the salt and pepper shakers were baby food jars with nail holes punched through the lid and the requisite grains of rice inside to absorb the moisture from Newport Harbor’s salty breezes.

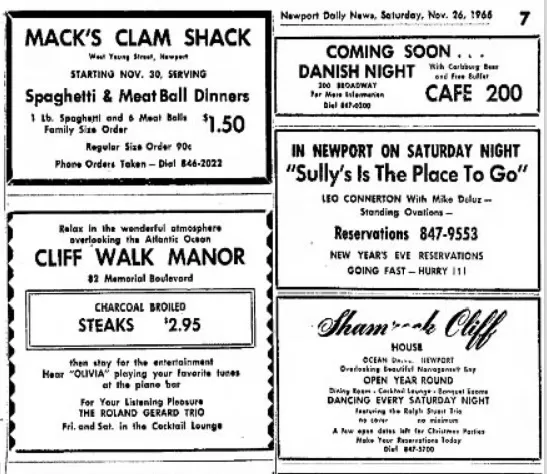

Ask anyone, and they’ll tell you Mack’s served generous portions for a bargain price. A 1966 advertisement in the Newport Daily News touts one pound of spaghetti with six meatballs for $1.50. The following year, fish and chips was just 60 cents. These — and the house-made coleslaw — linger in customers’ memories.

“It was like a weekly tradition for people in Newport,” says Nick Notarangelo, whose parents worked at Mack’s and had him shucking clams there when he was just six or seven.

Carlson says all her family members used the same recipes, and to this day she can cook them by memory. In a nod to her family’s legacy, the menu at Jo’s American Bistro includes two of Mack’s and Dry Dock Seafood’s most famous dishes: the fried fish sandwich and the fish and chips.

“I had to teach my executive chef, Brian Ruffner, whose degree is in culinary science, how to make it our way. I had to say, ‘I know this is counterintuitive to what you were taught in culinary school,’” she says. “Everyone just said, ‘Do it her way. It’s the best fish and chips I’ve had in my life!’”

For Carlson, being raised in restaurants in Newport has been a gift, giving her treasured memories she shares with the next generation. “[Restaurants] became my whole life — and my passion,” she explains. “I will do this to the day I wake up and it’s not fun anymore.”

Tucker’s Bistro: A distinctive flare and ever-evolving menu

2005–2012 | 150 Broadway

This unassumingly chic Broadway bistro charmed diners with its distinctive flair and an ever-evolving menu with French undertones. “Tucker’s was magical; just a little jewel on rough Broadway at the time,” says Susan Duca of Newport. “You walked through the doors and were transported to another place. It was artistic, like a dining salon, with paintings from floor to ceiling. Tucker made the place, too, with his larger-than-life personality.”

Tucker Harris was the bespectacled owner and maître d’ at his eponymous restaurant. “He was just such a character with those black glasses — very Truman Capote-ish,” recalls Deborah Bullock, a food blogger and former food columnist at the New Bedford Standard-Times. “I just remember walking in the first time and seeing all of these found objects that had been made into beautiful pieces of art.”

Tucker told guests his treasures were mostly from yard sales, from the vintage Jade-ite coffee cups and saucers to the iconic mismatched salt and pepper shakers, which live on at Malt on Broadway, the restaurant that operates in the same location today. “Chandeliers” made of chicken wire and white Christmas lights glowed overhead — but only subtly. The restaurant’s deep red walls and dramatic dark lighting rendered conditions so dim that small flashlights could be found on every table.

In the summertime, fans could be found on place settings for guests to keep themselves cool. Mirrors, statues and other oddities made dining at Tucker’s a multisensory experience.

Sandwiches in Rhode Island:

“It was just so overdone, and I think that was part of the appeal,” says Rick Allaire, who before opening Metacom Kitchen in Bristol was an executive chef at Tucker’s for many years. With Harris commanding the front of house, Allaire was given free rein in the kitchen.

“A lot of restaurants owners, myself included, want things a certain way. But when it came to the kitchen, he was very open to the chef doing what they wanted.” Allaire recalls from-scratch pasta dishes, a rotation of duck entrees through the years, and summer menus highlighting locally sourced seafood. “There was one dish that I did in the fall that I really liked: a seared foie gras with pumpkin seed oil, sumac caramel and roasted gingerbread. That was probably one of the best dishes I did there,” he says.

Bullock describes dining at Tucker’s as “adventurous,” noting its eccentricities both aesthetically and gastronomically. “The menu was incredibly eclectic compared to every place else on the island,” she notes. But there were two items Harris insisted be permanent fixtures on the menu: a digestif of Irish cream liqueur that Harris made himself, and the restaurant’s famed Thai shrimp nachos. In a nod to Tucker’s, Malt on Broadway continues to offer the latter today.

At Salas’ Dining Room you were treated like family

1952–2012 | 343 Thames St.

Salas’ Dining Room was a legendary Thames Street eatery for generations of Aquidneck Islanders. The food was good, the prices were affordable, and if you went to Salas’ you were treated like family.

“When I hear memories of people talking about the restaurant, it’s always about the early days and how the cost was so cheap to feed a family of eight. It was the only place people went with their families for special occasions because you could get spaghetti and meatballs and ‘the Oriental’ by the pound,” says Tonya Salas Mello, whose grandparents, Francisco and Maria (Mary) Salas, opened the restaurant in 1952.

“The Oriental” that Mello refers to is the restaurant’s most lauded dish, “Oriental Spaghetti,” which Francisco brought from his native Guam. “It was just Guamanian pancit with his own twist on it,” Mello explains.

“You could get anywhere from a quarter pound to two pounds,” says Dan Keirns, who was a regular at Salas’ during his teenage years (especially during football season). “We were big guys with big appetites.”

Dining rooms were on the second floor of the building, which was demolished in 2012 to build Midtown Oyster Bar. The restaurant didn’t take reservations, so patrons parked themselves on one of the reclaimed church pews or found a nook to wait for their name to be shouted out by the hostess. The décor was simple, with wood paneling throughout and tables dressed in traditional red-and-white checkered tablecloths. The operation was entirely a family affair, with Mello’s father, Frank, arriving early to get the sauce started, her mother, Sally, keeping the books, and aunts, uncles and cousins filling other roles.

There were so many employees working at Salas’ over the decades that it became hard to tell who were actual family members and who just felt like one. “We were there so long, customers became family too,” Mello says wistfully.

Michael Napolitano grew up going to Salas’ with his family and insists that every time they went, they ordered Oriental Spaghetti. “Anyone who grew up in Newport did!” he exclaims. Napolitano bought Macray’s Seafood in Tiverton in 2018 and this fall, he made Salas’-inspired Oriental Spaghetti a permanent fixture on the menu. Word of the addition has gotten around. “We get tons of people who specifically come here for the Oriental Spaghetti — people say they haven’t had it since Salas’ closed.”

Although Salas’ shuttered a decade ago, it doesn’t appear its legacy will fade anytime soon. Mello was at work one day and an employee of Midtown Oyster Bar came in and mentioned Salas’ restaurant. “I said, ‘Oh! That was my family’s business!’ and she said not a shift goes by that somebody doesn’t speak of Salas’, whether it’s about someone who worked there or a story from those days. That was great.”

Muriel’s Restaurant was a fixture on Spring Street

1985–1999 | 58 Spring St.

On any Sunday morning in Newport from the mid-1980s to the late 1990s, you could expect to see a long line of hungry diners stretching down Spring Street, far past the Touro Street intersection. Muriel Barclay de Tolly was serving up her huevos rancheros.

Barclay de Tolly was a fixture at her eponymous eatery, floating about while ensuring that the front of the house was in lockstep, customers were happy, and her treasured recipes were being executed properly. “Cooking was always something I enjoyed doing, and I had a lot of kids I had to cook for!” says Barclay de Tolly, 91.

“She led by example,” says her daughter Katie Potter, who worked at the restaurant like the rest of her siblings. “She was the type of manager and owner who would never ask you to do a job she wouldn’t do. Oftentimes, you’d have a dishwasher that didn’t show up, and she’d be back there washing dishes.”

In 1997, crew members from Steven Spielberg’s film Amistad were regulars at the restaurant, as was the director himself, who took such a liking to her hamburgers that Barclay de Tolly named one after him.

The scent of French toast and cinnamon buns would lure customers in early, while savory dishes such as pea soup, sausage and cheddar soup, and an apple, bacon and grilled cheddar cheese sandwich sautéed in brown sugar and butter attracted the lunchtime crowd. Dinnertime ushered in rich dishes like the Chicken Bombay.

“We did well,” Barclay de Tolly says with a smile.

There was one particular menu item that became the restaurant’s signature: seafood chowder.

The creamy concoction featured generous helpings of shrimp, scallops and scrod, and won first place at Newport’s Great Chowder Cook-Off so many times it was inducted into the Newport Chowder Hall of Fame in 1988. A 1990 New York Times article about Newport even made mention of it.

After an almost 15-year run, Barclay de Tolly sold the restaurant. “What I miss most are the wonderful people and friends who frequented my place,” she wrote in one of her two published cookbooks (in addition to five children’s books). Today, Barclay de Tolly’s daughter Katie operates the Newport Chowder Company, offering the same recipes via her food truck and a mobile cart.

Salas’ Oriental Spaghetti recipe

Serves 4–6

Ingredients

1 box linguini

1 pound pork, cut into strips

(tenderloin, if available)

Half a stalk of celery, sliced into small pieces

Half an onion (medium to large), cut into strips

1 large green pepper, sliced into strips

½ cup soy sauce

2 pinches Accent (optional, as Accent/MSG was not used by Salas’ in later years)

¼ teaspoon garlic powder

1 scallion, chopped

Precook linguini as directed on box, then rinse. Add a little oil to the pasta and refrigerate.

In a large frying pan or wok, cook the pork strips slowly. When the pork is thoroughly cooked, add celery, onion and green pepper. Toss and cook briefly — vegetables must stay crisp.

Reduce heat a little and add linguini, soy sauce, Accent (if using) and garlic powder, continually tossing until all ingredients are blended well and cooked linguini is heated through.

Garnish with chopped scallions and serve immediately with soy sauce on the side for those who prefer more.