Salve Celebrates 75 years: Leadership, Stewardship, Mercy and the Acoustics of Faith

By Betsy Sherman Walker

Salve Regina University marks its 75th year with a lavish (and lovable) book, an unbroken commitment to its roots and a strong sense of direction going forward

The story of Salve Regina begins in March of 1947 with the gift of Ochre Court to the Sisters of Mercy.

Designed in 1882 by Richard Morris Hunt for summer resident Ogden Goelet, Ochre Court was both a magnificent piece of architecture and a turn-of-the-century relic of Newport’s Gilded Age. The house had not been lived in for five years. Still, the transfer of the deed was significant enough to be reported in The New York Times. The headline read: “Robert Goelet Gives Villa to Catholics; Newport Ochre Court to be Women’s College.”

It may have been a match made in heaven, but it almost didn’t happen.

The estate was owned by Goelet’s son Robert, who in 1945 became involved in an ambitious proposal to establish the headquarters of the United Nations in Newport. The main building would be built at Fort Adams, and other remnant summer cottages on and off Bellevue Avenue (among them Ochre Court, The Breakers and Marble House) would be repurposed as embassies and offices. That plan fell through when Newport was deemed too inaccessible. Goelet then offered the house to his daughter, who was not interested.

“Salve was actually Plan C for the Goelets,” says John Quinn, Chairman of the Salve History Department.

In 1934, the Sisters of Mercy, a religious order in Providence with its Mother House in Cumberland and 19th-Century roots in Dublin, was granted a charter to open a woman’s college in Rhode Island.

According to Quinn, the Sisters already had a toehold in Newport, with parish schools at both St. Mary’s and St. Augustine’s churches, and an orphanage, the Mercy Home — which was located on the current-day site of the Community College of Rhode Island campus in the North End.

However, it was not until Cornelius Moore, a prominent Newport attorney, stepped in and, via Providence Bishop Francis Keough, put the Sisters in touch with Goelet. Moore, a founder of Portsmouth Priory (now Portsmouth Abbey School), was a good Catholic; Goelet, a well-heeled New Yorker, was a good Episcopalian.

“Goelet never had any connection with the Catholic church,” says Quinn. “He just had an Irish-American lawyer. Moore was the conduit.”

In early March of 1947, Bishop Keough and the sisters traveled to Newport for a look-see.

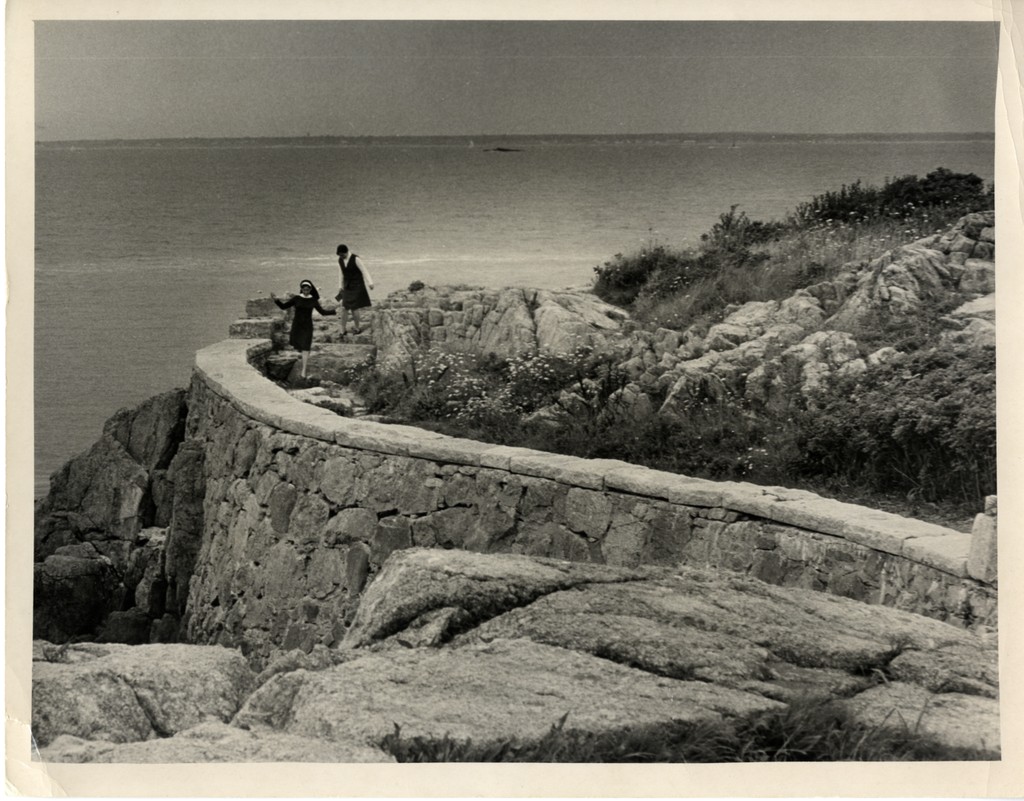

Despite that, to quote Quinn, “the sisters thought Newport was on the other side of the moon,” the decision seems to have been made on the spot. On March 21, 1947 The New York Times reported the donation of the “fifty-room villa on Cliff Walk at Newport, to the Catholic Diocese of Providence.” Altogether, the six acres of land and the house were assessed at $312,000.

And with that, after more than a decade, the Sisters of Mercy’s college had found a home.

“They were able to transform it in six months,” said Quinn. “It needed repair — and they needed to get it ready. It was a real scramble.” Still, the following September, Salve Regina College (Latin for “Hail, Queen”) opened, with a freshman class of 58 young women pursuing degrees in Nursing, the Liberal Arts, and Home Economics.

Good Turmoil

With a devotion that was in equal measure religious and activist, the school began to blossom.

In 1955, Salve acquired both Moore Hall (a gift from, and named for, Cornelius Moore) and McAuley Hall (the Vinland mansion, donated by a member of the Vanderbilt family), which was named for Catherine McAuley, who founded the Sisters of Mercy mission in Dublin in 1831 to aid the needy and promote social justice.

“The key hoop,” Quinn said, “was gaining accreditation in 1956.” Once the school was accredited as a viable college, enrollment started to increase. The next decade saw the addition of Miley Hall in 1964 as a freshman dorm and the O’Hare Academic Center in 1968.

Against the backdrop of post-World War II Newport, Salve set its roots. In those days, the town, according to Quinn, “just wasn’t that prosperous. It was a Navy town, it was gritty.” It had not yet been reinvented as the City-by-the-Sea we think of today.

M. Therese Antone, RSM graduated from the college in 1962 with a degree in Mathematics (“RSM” refers to her order: Religious Sisters of Mercy). She returned in 1976 to join the administration, eventually becoming the school’s sixth president and current chancellor.

“I can recall, back to 1973, when the Navy Fleet pulled out,” Sister Therese said. “But we hung in there,” she added. “We grew in stature and enrollment — and contributed to the social, economic, and cultural life in Newport.”

The once-small women’s college without a home is now a coed institution with an enrollment of 2,800 students, 10 main buildings, and 80 acres of spectacular Newport property. This year, the school offered 46 majors, 42 minors, 13 master’s programs, on and offline, and three doctoral programs — International Relations and a Doctor of Nursing Practice among them. Other masters are available in Leadership and Business, Humanities and Creative Arts, and Counseling and Psychology.

With the establishment of the Pell Center for International Relations and Public Policy, launched in 1996, Salve acquired international stature. Over the years, campus lecture halls have resonated with the words of the Dalai Lama, Elie Wiesel, David McCullough, Cornell West, Supreme Court Justice Elena Kagan and Dr. Jill Biden.

The 1960s, Quinn said, brought “turmoil” to the campus — but for the most part it was good turmoil.

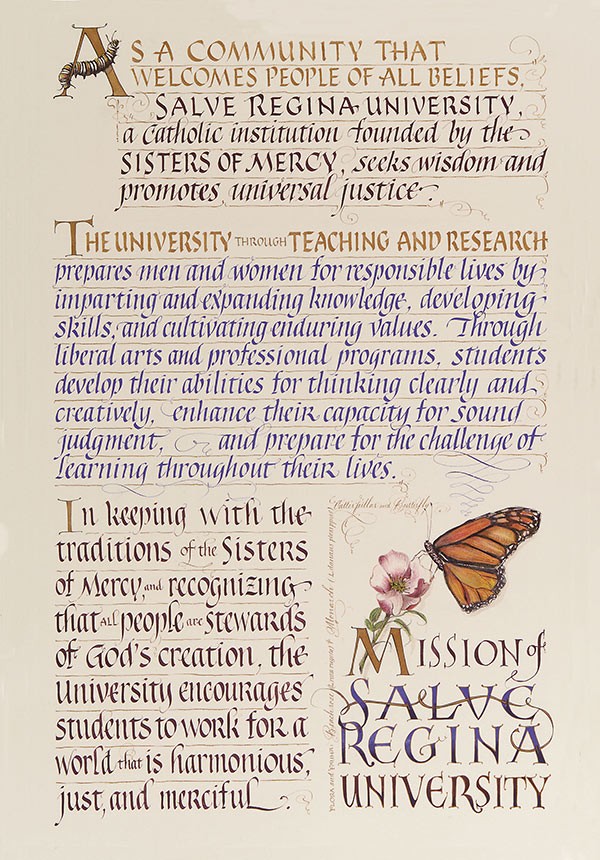

“We’ve always been very involved in quiet ways,” Sister Therese said. The sisters embraced social activism encouraged by a network of school leaders who remained loyal to the Mercy Mission, which begins: “As a community that welcomes people of all beliefs, Salve Regina University, a Catholic institution founded by the Sisters of Mercy, seeks wisdom and promotes universal justice.”

References to it are everywhere, from the school’s website to the art around campus, to the conviction with which faculty and staff speak about the community — the Mercy Mission seems woven into an everyday way of being.

In 1968, Sister Mary Christopher O’Rourke was named president, after serving as chairwoman of the sociology department. “The college was very involved in the Head Start program and New Visions of Newport County because of her,” Quinn said.

It was also during O’Rourke’s tenure that the conversation of going coed began to surface.

Sister Therese said that by the late 1960s, enlisted men from the Navy were already taking classes there. In the 1970s, Salve introduced its Criminal Justice program, which in its early days was mostly comprised of male police officers and state troopers.

On the heels of Sister Christopher came Sister Lucille McKillop in 1973, a scholarly mathematician who saw co-education as both a cultural and financial inevitability.

“She wasn’t even in the door as president,” said Quinn, “when she said, ‘We’re going coed.’” McKillop’s tenure lasted until 1994, during which time enrollment more than doubled (from 1,000 to 2,300), and the number of majors increased from nine to 25. She introduced graduate programs in business and accounting. And, under her leadership, in 1991 Salve earned university status.

A beloved fixture in the community, in 1980 McKillop was the first woman — and first nun— to preside as Grand Marshal at Newport’s St. Patrick’s Day parade.

Sister Therese followed Sister Lucille in 1994. “I had already been at Salve,” Sister Therese said, “and I knew it uniquely.”

Her goal was to make sure the foundation thrived and to foster a campus culture that was “steeped in mercy.” As with the sisters who came before her, Sister Therese’s life is steeped in mercy, and to live in a just way is her personal mission and calling. She retired in 2009 and segued into the position of university Chancellor.

Sister Therese is still very much a woman about campus.

Now, Sister Therese also has a building in her name: the Antone Academic Center, a reconfiguration of four existing buildings, combining the stables from Chateau-sur-Mer and the carriage house at Ochre Court, which houses the Art, English, Dance and Theater departments.

On The Map

Sister Therese well remembers the day in 2005 when the Dalai Lama came to visit.

A few years after the Pell Center for International Relations was established in 1996, a conversation with its namesake, Senator Claiborn Pell, put the ball squarely in her court: “‘There’s one thing I’d like,’” she recalls the Senator telling her, “I’d like you to get the Dalai Lama to come to Newport.’”

She promised she’d try.

It took three years, but sure enough Sister Therese was able to arrange the visit.

The Dalai Lama arrived with an entourage, but the two managed to have lunch alone. They covered a multitude of topics. “He wanted to know what it was like to be [an everyday] religious, [able to be] out in the world,” and not be the Dalai Lama. “He was easy to talk to,” she said. “Very charming — playful too. And very profound.”

Pell and the Dalai Lama had already established a “deep friendship,” she said. It had been a few years since their paths had crossed, and Pell’s Parkinson’s Disease had progressed. Sister Therese witnessed “the most tender moment, when he and the Senator came together.” It was the first time the Dalai Lama had seen Pell in his wheelchair. “Both of them burst into tears,” she said. “It was a very emotional moment. I’ll never forget it.”

Sister Jane Gerety was president from 2009-2019. Her vision for the school opened Salve’s academic doors to a broader base of disciplines — adding a doctoral program in nursing and an MFA in creative writing; to business and research in the sciences. Sister Jane was also a skilled fundraiser; under her leadership she oversaw the $26 million renovation of the O’Hare Academic Building, increased the endowment, and doubled the monies raised at the annual Governor’s Ball to more than $500,000.

‘The Things They Sometimes Don’t See’

Salve’s campus is consistently ranked as one the most beautiful in the country. But therein lies the rub. Those who know it best feel that its beauty, while undeniable, tends to outshine its academic muscle.

The students might come for the beauty, said biology professor Dr. Jameson Chace, but they are transformed by the education. A devoted conservationist who serves on the board of the Audubon Society of Rhode Island, Chace is also chairman of the Cultural, Environmental and Global Studies department.

He said he watches students “spend four years inside a classroom,” so he does what he can to open their eyes to “the things they sometimes don’t see.” (He is also remembered for being that professor who paused in the middle of a commencement address to identify the bird song of the Yellow Warbler loudly chirping in a tree overhead).

Chace did not coin the term Living Laboratory, but he preaches and teaches it. “Mornings at Green Bridge, going out in a Boston Whaler, pulling up traps; that moment when the student becomes part of the process, getting up in the predawn hours — they become experts,” he said. “They want to pass on the knowledge. The living laboratory is what allows that to happen. [So often] on a college campus, there is no connection to the community.”

On the day “Newport Life” chatted with current Salve president Dr. Kelli Armstrong, efforts were underway to organize a Valentine’s Day vigil for the earthquake victims in Syria and Turkey. Similar humanitarian efforts, she said, have been ongoing for Ukraine since last spring.

Armstrong, the first lay president as well as the first working mother, has been at Salve since August of 2019. A newcomer to Newport, she is enamored of the 75-year-old institution and both the resiliency and resonance of its mission.

Armstrong feels that she arrived at a crossroad in the school’s history.

The Sisters of Mercy, she says, are still active everywhere. But their way of life is “aging,” and she feels that it “was important for a lay president who could integrate the mission into a more secular world and secular lives.”

With her eyes set firmly on the future, Armstrong sees one of Salve’s strengths as its flexible interpretation of the past.

There is a vibrant LGBTQ culture on campus, she says, and an active LGBTQ center. The broader strokes of diversity and inclusivity as well define what she sees as “the more inclusive model set by Christ.”

Within six months of Armstrong’s arrival, the pandemic followed. “Poor Salve — they got a rookie!” was how she felt people viewed the situation.

Yet if there was a gift in such an unwelcome disruption, she made the most of the unexpected time on her hands to develop COMPASS, a pilot program blending academics with internships and workplace experience designed to make a Salve degree both relevant and marketable.

Her vision worked; COMPASS has been so successful that the Board has voted to endow a position, and the school received a Van Beuren Foundation grant to house it.

Armstrong, like Chace, is all about “the things they sometimes don’t see.” The school’s “biggest Achilles heel,” she said, “is people not knowing about it.” Sister Therese would agree, saying that she often thought that the school hadn’t been appreciated the way it should. “It’s more recognized outside of Newport for its preservation efforts than inside,” she said.

From the outside looking in, however, entering the campus of Salve under the canopy of its arboretum-worthy trees, is something akin to entering an 80-acre chapel. Mercy and education continue to resonate with the things we don’t see — the acoustics of some deeply-held faith — as they have since day one.

“Our Gen Z students do want to make a difference,” says Armstrong. “Because of them I have great hope for the future — that they will bring us home.”

Living Laboratory; a Living Cathedral

By the start of the 21st Century, the Salve campus had grown to 60 acres with 18historically significant buildings. In 1999 it received a National Preservation Award from the National Trust for Historic Preservation; in 2000 it received an Historic Preservation Award from the Rhode Island Historical Preservation and Heritage Commission; and in2002 a Getty Grant Program honor that would enable it to create a campus heritage preservation plan.

It is also a tree museum. Many of its landscaped grounds were laid out more than a100 years ago, on the great lawns of some of the great summer houses, designed by the famed Olmsted brothers’ landscape architectural firm. The 80-acre campus, with 1,460 carefully tended trees of more than 150different species earned it a Tree Campus USA designation in 2015.

The Arboretum is even included in “Muse and Mercy” as one of the 75 treasures on the campus, with a tribute by biology professor and academic tree-whisperer Dr. Jameson Chace. “Each tree,” Chace writes, is “a brushstroke in the campus as a work of art.” The casual observer, he says, is “unaware of the careful stewardship required for cultivating a botanical tree garden.”

In 2016, Salve was accredited by the Morton Arboretum (“the Champion of Trees”) as a Level II arboretum; in 2018 Chace’s students submitted a 10-year plan to reach Level III status, which requires a minimum of 500 species under the care of a dedicated curator.

Muse and Mercy

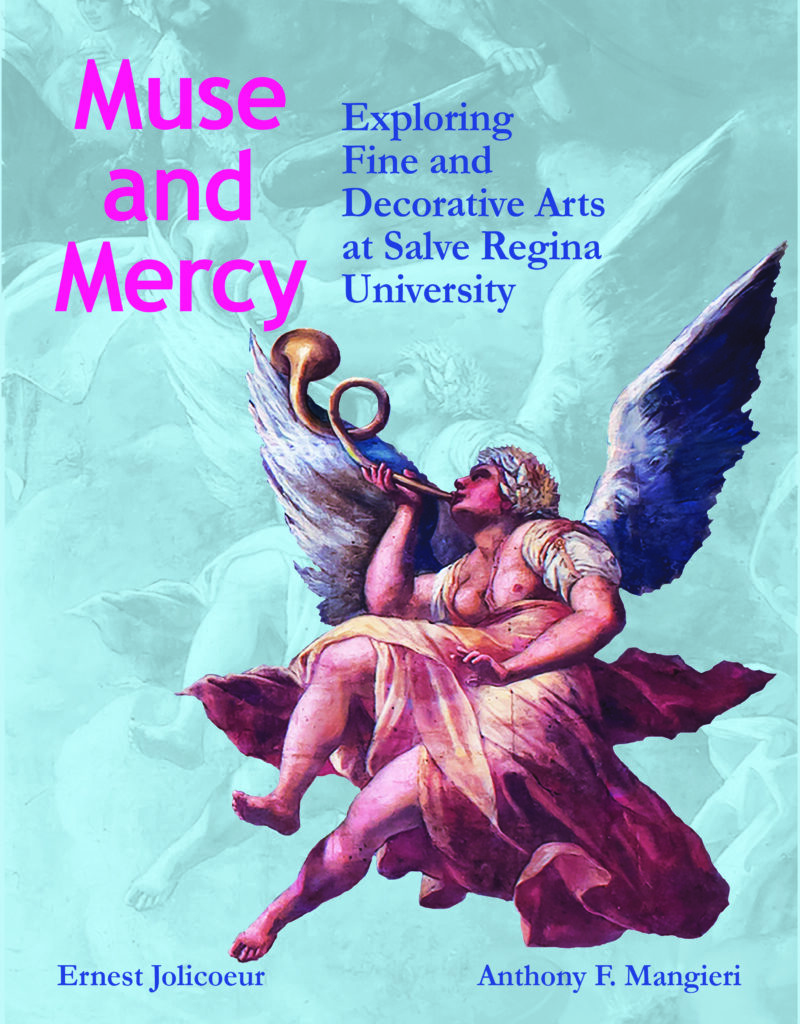

There are many events being planned on Salve’s campus to celebrate its 75th year. But there is a good chance that “Muse and Mercy,” the coffee table-worthy book compiled by art department professors Anthony Mangieri and Ernie Jolicoeur, which features 75works of art located around campus, all beautifully photographed, is the gem with a capital G.

An 18-month labor of love, Mangieri calls the book an “open invitation” to immerse oneself interactively in the artwork that defines the campus community — indoors and out, secular and religious, Rococo to Japanese; gargoyles, grotesques, and mermaids; portraits(including one of Ogden Goelet) and stained glass.

“I’m always interested in the narratives behind them,” Mangieri says of the work, “and also in their context.” The two joined the Salve art department the same year, in 2011.

“Anthony and I had done projects before and discussed the possibility of writing a book together,” explains Jolicoeur. “Our courses were always looking outwards. This time, we were looking inwardly. We had no idea of what was there.”

Among their finds: Rococo murals in a private office (they had to wait until the summer to gain entry — and find a security guard to let them in), as well as a Raphael portrait on glass that was tucked away behind a soda vending machine. Outside, there is an oversized C. 200B.C. Roman urn and a life-size statue of the original Mercy sister, Catherine McAuley.

“Muse and Mercy” is for sale on the university’s website at salve-regina-university-commemorative-gifts.myshopify.com. The cost is $75.