The Story of Newport: An African heritage perspective

By Keith Stokes

African heritage people have played a significant role in Newport’s history for centuries

Perhaps the most transformative event to shape the settlement, economic, religious, and cultural growth of the Western Hemisphere has been the introduction of African bondage, which lasted for nearly four centuries.

Only a tiny fraction of the approximately 12 million enslaved Africans brought to the New World during that era would end up in North America, with the vast majority of the enslaved shipped to South America and the West Indies. The first of these “forced immigrants” arrived in the Colony of Rhode Island sometime around 1652, and the first documented slave ship, the “Sea Flower,” arrived in Newport in 1696.

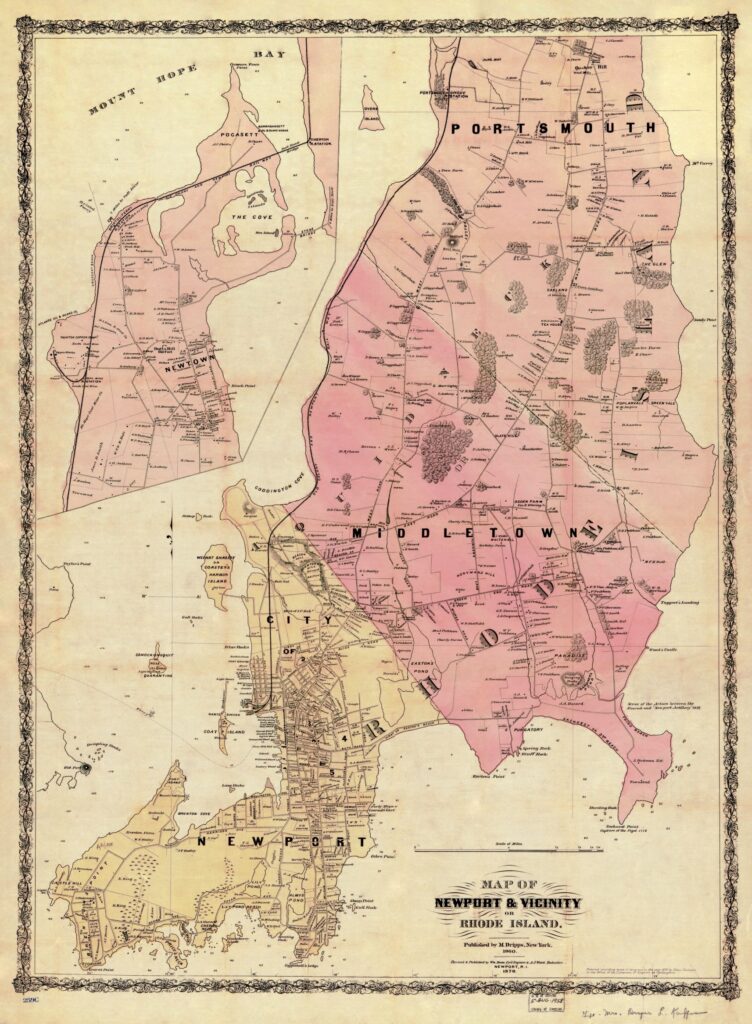

The African Slave Trade and Newport share common origins. Newport, one of the American Colonies’ most prosperous seaports, experienced unprecedented growth during the 17th and 18th Centuries, mainly through the production and export of rum, spermaceti candles, codfish, and enslaved African men, women and children. Many enslaved Africans that arrived in Newport originated from the Guinea, Gold, and Cape Coasts of West Africa. Many would also come to Newport from West Africa via Barbados, Antiqua, and Jamaica.

Between 1700 and 1775, what historians commonly called Newport’s “Golden Age,” the African trade dominated nearly every aspect of the Newport maritime economy. As early as 1708, enslaved Africans outnumbered white indentured servants in Newport 10 to one. By 1755, Africans comprised nearly 15% of the population of Newport, and by 1774, two dozen rum distilleries were operating along the Newport waterfront, producing much of the world’s market of “Guinea Rum.” A Negro burying section of the Common Burying Ground was established as early as 1705, and it later became known to the African heritage community as “God’s Little Acre.”

But African life in Colonial Newport was not without opportunities.

Historical records of the time reveal a Newport maritime trade economy largely dependent upon the skilled work of Negro, Indian, and Mulatto servants (enslaved people). Many Africans, both enslaved and free, became a part of the skilled labor force in many trades, including cord winding, barrel making, stonemasons, carpenters, furniture makers, shipbuilding, rum making, chocolate grinding, candle making, and silversmiths.

These skilled trades, which required levels of education and craft training within the slave economy in Newport, would create a distinct difference between slavery in Colonial Newport as compared to the American South and West Indies. Several of America’s most historically significant colonial structures still standing today were constructed by highly skilled artisan labor, including free and enslaved Africans. Newport’s historic buildings include Touro Synagogue, the Redwood Library & Athenaeum, Brick Market, and the Old Colony House.

Africans as Americans: Freedom & Interdependent Living

By the mid-18th Century, as Newport Africans lived, worked, and worshiped “interdependently” with the owner class, many would eventually achieve freedom either by manumission or through work and self-purchase.

Beginning as early as 1756, enslaved and free Africans would assemble at the public commons at the corners of Thames and Farewell streets (the future site of the Liberty Tree)to hold elaborate multiple-day ceremonies, where they would vote for and elect a Tribal Chief — or what the white community termed the “Negro Governor.” The election was held in June of each year, and any African owning a pig was eligible to vote.

These highly festive ceremonies were a combination of African and European traditions. After the election votes were tallied, the new African Governor would be honored in an inaugural parade accompanied by food, games, socializing, and dancing to celebrate the African community. This tradition is also seen in Boston, Hartford, Salem, and Portsmouth, N.H.

A pivotal historical moment and opportunity for free and enslaved Africans came on Nov. 10, 1780, as a group of free African men assembled in Newport at the Levin Street home(today’s Memorial Boulevard West) of Abraham Casey to organize and charter America’s first mutual aid society for Africans — known as the “Free African Union Society.”

The Society’s lofty mission included providing funds for indigent families, a burial society to ensure proper burials, setting moral and ethical standards for public conduct within the larger community, and, most importantly, raising consciousness and funds within the African community to someday return to their native Africa.

Meeting minutes of the Society that still exist today describe in detail the efforts to promote the betterment of fellow Africans, enslaved and free. Newport would advance similar African societies in Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Providence. Not to be outdone, Newport’s African women, led by Obour Tanner and Sarah Lyna, would establish the “African Female Benevolent Society” in 1809.

Continuing its mission in Newport, the African Society would establish one of the nation’s earliest free African schools organized, supervised, and taught by fellow Africans. A March25, 1808, notice in the Newport Mercury newspaper advertises the availability of a school for all African persons in Newport at no charge to students.

Early 19th Century Newport: Freedom & Settlement

The years immediately after the American Revolution were difficult for Newport. Years of war had greatly stifled the maritime trade economy. During their occupation of Newport, the British and Hessian troops destroyed many buildings and deforested much of the island’s natural trees. By 1800, many now-free African heritage residents were leaving the city for employment and living opportunities in more-prosperous cities, including New York, Boston, Philadelphia, and Providence. During the early 19th Century, the city’s population of African heritage was a fraction of what it was during the years leading up to the American Revolution.

The center of the remaining African heritage community was the civic and educational activities within the African Union Society, soon renamed the Free African Benevolent Society. In 1824, the Society completed its evolution and became charted as the Union Colored Congregational Church, Newport’s first African heritage church. The church was one of the first with a solely African administration, operational charter, and congregation.

Located on Division Street, the community became the center of 19thCentury African heritage religious, civic, political, and cultural life in Newport. Many congregants lived near the church, mostly in what is called today the “Historic Hill” neighborhood of Newport, including Division, School, Mary, John, Levin, Cannon, Williams, and Thomas streets, and along Bath Road. Another area with several persons of color living in their homes is Pope Street between Spring and Thames. During the early 19th Century, this section was called “Negro Lane.”

The early 1840s brought two significant events for the African heritage community of Newport.

In 1842, at the November session of the Rhode Island General Assembly meeting at Newport, the Rhode Island Constitution was revised and ratified, granting African heritage men, among others, the right to vote.

Four years later, African heritage businessman George T. Downing arrived from New York and opened a restaurant on Bellevue Avenue in Newport to cater to the emerging summer resort market. Over the next10 years, Downing would build and operate a series of highly successful hospitality businesses that exclusively catered to the fledging summer trade. Downing would also run the Sea-Girt Hotel along Bellevue Avenue with amenities, including fine dining, catering services, and accommodations for gentlemen, boarders, and families. The businesses occupied a block across from Touro Park that still bears his name: The Downing Block.

While the Civil War was raging, Downing led a group of Newport and Providence African heritage leaders to call for equality in public education. At a March 1863 meeting at the Union Congregational Church, Downing led a strategy for legislation to fully integrate public schools in Rhode Island. He would succeed in this effort, as all schools would be integrated by 1867.

Late in 1869, the Reverend Mahlon Van Horne assumed the pastorate of Union Congregational Church in Newport. Van Horne brought a new style of preaching that blended religious convictions with civic and political responsibility. He quickly became a protégée of George T. Downing, and they became activists in the local, state, and national Republican Party.

In 1872, with the help of Downing and famed Abolitionist — and Point resident — Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Van Horne became the first African heritage member of the Newport School Board. In 1885, he was elected as the first person of color to the Rhode Island General Assembly. In 1896, President William McKinley appointed Van Horne to be U.S. Consul to St. Thomas in the Danish West Indies, where he played a crucial role during the Spanish-American War.

Van Horne would become a role model for future Newport African heritage religious leaders during the 19th and early 20thcenturies who utilized the pulpit to provide spiritual comfort and promote social justice. In Van Horne’s footsteps were Reverends Henry Jeter and Byron Gunner of the Shiloh Baptist Church, Peter Quire, the founder of St. John’s Episcopal Church, and Reverend James Lucas of the Mt. Olivet Baptist Church.

Newport’s Gilded Age of Color

Newport is internationally recognized for its Colonial Era structures, Gilded Age mansions, historic landscapes, and deep maritime history. However, Newport also hosted many key African heritage business entrepreneurs who would leverage their commercial enterprises to promote economic security and build wealth to invest in and advance African heritage civic, recreational, social, and political interests.

Unsurprisingly, African heritage leaders in commerce would also become leaders within their community to promote equal rights and civic and political leadership. The city’s earliest African heritage doctors, dentists, teachers, hospitality entrepreneurs, and elected officials appeared during the Gilded Age.

After the Civil War and remaining strong through the early20th Century, particularly during the Gilded Age summers, Newport became a magnet for leading African heritage families attracted to the numerous civil rights and social uplift organizations led by the Women’s League Newport (1895), Sumner Political Club (1898), and the Newport Branch NAACP (1919).

Men, women, and families of color would travel from Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Washington to take part in a rare opportunity for persons of color for unrestricted social and cultural interchange. Newport was host to abundant African heritage social and political gatherings that ran the broad spectrum of political rallies, social events, and religious revivals.

The Colored Washington Newspaper in 1886 described a Newport summer experience, reporting, “If there was a watering place in America where respectable, refined and well-bearing colored ladies and gentlemen have as little reason to feel their color as in Newport.”

This era also unveiled a new generation of influential African heritage men and women who would become leaders in medicine, arts, and government.

Dr. Marcus Wheatland of Barbados arrived in 1896 and became the first known African-heritage physician to live and practice in Newport. Dr. Wheatland gained a national reputation as one of the first medical doctors to employ the X-ray as a diagnostic tool.

Dr. Alonzo Van Horne, son of Reverend Mahlon Van Horne, graduated from Howard Medical School in 1897 and became the first African heritage dentist in Newport, practicing at 47John Street and later at 22 Broadway.

Both men were also active in civic and government affairs, with Wheatland becoming an early African heritage city councilmember and Van Horne leading the African heritage Masonic Order.

During the early 1930s, Dr. Daniel Smith established a general medical practice in Newport at his Mary Street home and office. And Dr. Harriet A. Rice, born in 1866, would live and practice medicine for a considerable amount of her career at the family home at 75 Spring Street. Rice would achieve fame as the first African heritage woman to graduate from Wellesley College in 1887.

Newport’s late 19th and early 20th-century African heritage community also highly valued the arts.

Artists like painter Edward Mitchell Bannister, the Providence Art Club and Rhode Island School of Design founder, would frequently summer in Newport, with Aquidneck Island landscapes becoming some of his famous works.

William Stanley Beaumont Braithwaite was a nationally renowned poet and literary critic who married Newporter Emma Kelly and had a summer family home on DeBlois Street. He would lead many academic and social discussions within Newport’s trendy African heritage Men’s Club.

In the early 20th Century, dozens of African American civic, social, and fraternal organizations were established, many associated with church groups. Leading organizations included the Odd Fellows, B.F. Gardner Commandery, Knights of Pythias, Households of Ruth, Sheba Court #3, Queen Ester Lodge #11, Heroines of Jericho #3, Boyer Lodge, Hope Lodge, and Stone Mill Lodge. The Women’s League Newport, led by dynamic businesswomen Mary Dickerson, would play an essential role in promoting the welfare of women, children, and families.

During the First World War, Newport was at the center of activity with Navy training and torpedo design and production activities. Many of Newport’s African heritage men came forward to heed their country’s call for service.

In 1919, led by Reverend James Lucas of the Mt. Olivet Baptist Church, the Newport Branch of the NAACP was organized with an initial focus on supporting the returning African heritage veterans who faced employment and housing discrimination — and to combat lynching, which was the most critical issue facing people of color at the time across the nation.

In 1932, Newport political activist William H. Jackson was appointed Sergeant-At-Arms at the Republican National Convention, where he led an anti-lynching platform. The Great Depression would significantly affect Newport, where many businesses dependent on the seasonal resort trade were forced to close. The Great Depression also ended the opulence of the Gilded Age.

To The Future

After World War II, African heritage residents continued to contribute at all levels, including our first African heritage Mayor, Paul Gaines, who was later joined by residents of color who became contributing members of local and state government, business, and social service organizations.

The religious spirit of the original four African heritage churches lives on in the Community Baptist Church, and there is not a historic neighborhood in the city that does not have a home that was once owned or lived in by 18th and 19thCenturyfamilies of African heritage.

Today, the God’s Little Acre section of the Common Burying Ground has been nationally recognized as having the oldest and largest surviving collection of markers of enslaved and free Africans, the earliest of whom were born during the early years of Newport’s settlement.

Since the founding of Newport in the early 17th Century, Newporters of African heritage have lived, worked, and worshipped in this historic city. While their path to prosperity included overcoming the trials and tribulations of human bondage and discrimination, they would persevere and significantly contribute to the economic, civic, and social fabric of our historic “City-by-the-Sea.”